Patient case: From treatment to complication, a cautionary tale about the risks of mitomycin C 8 years later

The contents of this article are informational only and are not intended to be a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment recommendations. This editorial presents the views and experiences of the author and does not reflect the opinions or recommendations of the publisher of Optometry 360.

By Kaleb Abbott, OD, MS

Introduction

This case describes a relatively uncommon, yet serious, side effect of the commonly utilized antimetabolite mitomycin C, which induced focal scleromalacia perforans and avascular necrosis 8 years after an Ahmed valve implantation.

Scleromalacia perforans, first described in 1893 by Holthouse and later defined by van der Hoeve in the 1930s, was initially considered extremely rare and only associated with rheumatoid arthritis.1 Present day, scleromalacia perforans is still found in cases of adult-onset rheumatoid arthritis2 and juvenile rheumatoid arthritis3 but is also recognized to occur in severe cases of other systemic conditions such as Wegner’s granulomatosis,4 Crohn’s disease,5 ulcerative colitis,6 systemic lupus erythematosus,7 and relapsing polychondritis.8 It is a subset of scleritis characterized as anterior necrotizing scleritis without inflammation, which accounts for only about 4% of scleritis cases.9

While scleritis generally presents with symptoms of severe dull pain, eye redness, tearing, and photophobia, scleromalacia perforans often present with minimal symptoms of redness, pain, or edema. The classic example case of scleromalacia perforans is an elderly woman with chronic rheumatoid arthritis and minimal eye symptoms. Scleromalacia perforans presentation may consist of atrophy of the episclera and episcleral vasculature, thinning of the sclera and associated vasculature, and blue scleral hue indicative of visible underlying choroidal pigment.10 Scleromalacia perforans is thought to occur due to scleral fibrocyte activation, cellular matrix resorption, scleral stroma infiltration by inflammatory cells, and prolonged vaso-occlusion.9

Here we recount a case of scleromalacia perforans with avascular necrosis 8 years after exposure to mitomycin C.

Case presentation

A 45-year-old white male presented to the clinic with soreness and mild pain in his right eye for 2 days without photophobia or changes of vision. His current ocular medication included 0.05% difluprednate twice daily in both eyes, dorzolamide/timolol twice daily in both eyes, and 0.5% timolol maleate twice daily in both eyes. Past ocular history included bilateral idiopathic para planitis, bilateral uveitic glaucoma, bilateral pseudophakia, bilateral posterior vitreous detachments, and bilateral epiretinal membranes. Past ocular surgical history included a RETISERT® (fluocinolone acetonide intravitreal) implant 9 years prior in the right eye, cataract extraction and intraocular lens implant of both eyes, Ahmed valve implantation of the right eye 8 years prior, Ahmed valve implantation of the left eye 7 years prior, and surgical peripheral iridotomy of the left eye.

In recent years, his para planitis recurred when using less than 2 drops of 0.05% difluprednate daily. He had an unremarkable past medical history and was not taking any systemic medications. At the time of his diagnosis of para planitis 14 years earlier, he underwent Lyme, rapid plasma reagin, fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption, angiotensin-converting enzyme, serum lysozyme, chest X-ray, and Mantoux tuberculin skin test testing, all of which were negative.

Vision with spectacles was 20/30 in the right eye and 20/25 in the left eye. Intraocular pressure measured with Goldmann Applanation was 8 mmHg and 6 mmHg in the right and left eyes, respectively. There was no afferent pupillary defect. Confrontational visual fields and extraocular movements were both full.

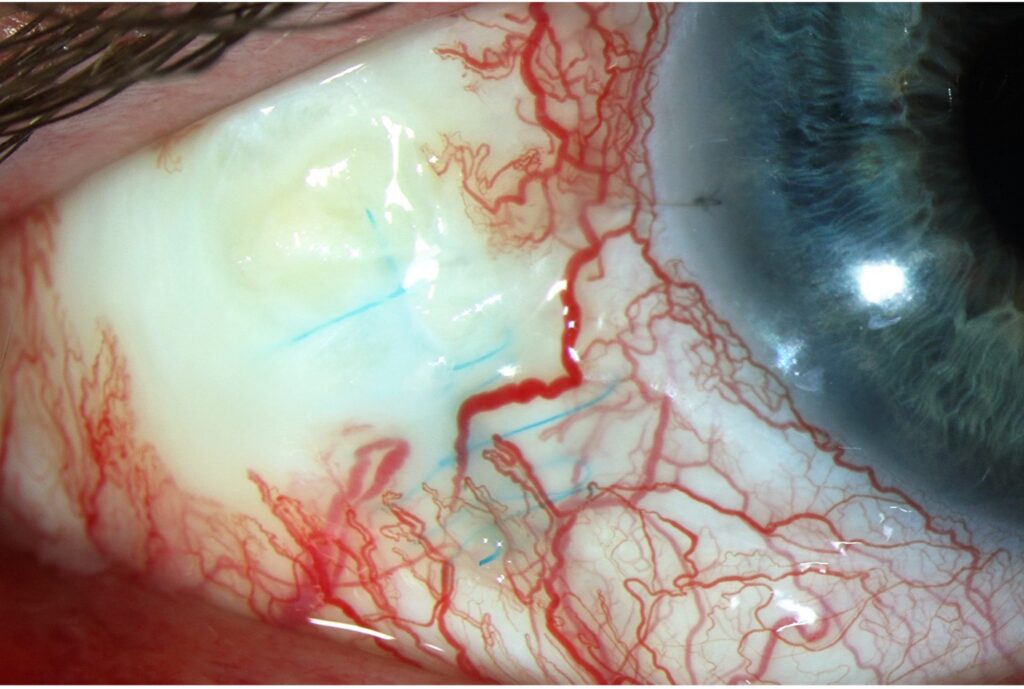

Slit lamp examination of the right eye revealed temporal ragged scleral thinning with absent overlying bulbar conjunctiva at the RETISERT® implant site with exposure of underlying prolene sutures. The temporal sclera demonstrated 25% thinning, a large area of avascular necrosis, and calcification (Figure 1). The bleb located superior temporally had overlying conjunctiva. There was no mucoid discharge or evidence of infection. There was an intact loop suture at 9:00 in the cornea and an Ahmed tube at 11:00 in the anterior chamber. There were trace cells in the anterior chamber and the vitreous. Dilated fundoscopic examination revealed the RETISERT® implant had detached from the strut and was mobile in the inferior vitreous. The cup-to-disc ratio was 0.75, peri-papillary atrophy was visible around the optic nerve, and there was a tuft of fibrous tissue attached to the optic nerve. The patient was started on moxifloxacin 4 times per day in the right eye for infection prevention.

A thorough records review concluded that the most likely cause of the scleromalacia perforans and avascular necrosis was prior use of mitomycin C during the Ahmed valve implantation 8 years prior. Given the compromised globe integrity, a scleral debridement of the necrotic tissue, cadaveric scleral patch graft, vitrectomy, and removal of the RETISERT® implant and strut was performed. The conjunctival epithelium healed within 2 months, and no further scleral thinning occurred. In subsequent visits, the patient reported less eye soreness, and the globe was structurally sound with no risk of perforation or infection.

Discussion

Discovered in Japan in 1954, mitomycin C is an antibiotic and alkylating agent isolated from Streptomyces caespitosus.11 Its mechanism of action involves the crosslinking of adenosine and guanine in DNA molecules thus inhibiting DNA synthesis and cell mitosis.12 In ophthalmology, it is used in glaucoma, conjunctival, cornea, anterior segment, and refractive procedures13 to inhibit fibroblast proliferation, reduce scarring, mitigate extracellular matrix production, and suppress vascular ingrowth.14 Mitomycin C has demonstrated rare but serious complications including scleromalacia, scleral calcification, corneal ulceration and perforation, iritis, secondary glaucoma, hypotony, conjunctival leak, fungal infection, endophthalmitis, and sudden onset mature cataract.15 Risk of complications is dose and time dependent.16 Complications are thought to arise due to mitomycin C being toxic to both fibroblasts and vascular endothelial cells.17 The earliest cases of mitomycin C-induced scleromalacia perforans were reported by Mermound and Akova.18,19

Scleromalacia perforans is characterized by thinning of the sclera and may be accompanied by an absent bulbar conjunctiva and avascular necrosis. If left untreated, it may progress to a globe rupture, although this is uncommon. Other complications include vision loss secondary to irregular astigmatism, cataracts, secondary glaucoma, and uveitis.9

While mitomycin C is not routinely used in Ahmed valve implantations presently, it is still utilized in other glaucoma surgeries such as trabeculectomies as well as surgeries for pterygiums, ocular surface tumors, laser refractive error correction, dacryocystorhinostomies, and strabismus surgeries.13

The etiology of this case differs from similarly reported cases in multiple ways. Firstly, the scleral melt did not occur in the primary location in which the mitomycin C was utilized, but rather directly anterior to a RETISERT® implant, which provided local and continuous corticosteroid exposure in addition to long-term topical difluprednate exposure. Secondly, there was a lengthened duration of time from the mitomycin C exposure to the scleral thinning. Thirdly, there was a potential role of mechanical friction from the RETISERT® implant on the scleral melt. The combination of such factors leading to focal scleromalacia perforans and an avascular necrosis has not been reported in the literature. No underlying systemic cause is suspected due to a negative initial comprehensive uveitis work-up and no systemic disease manifestations during the 14 years from the pars planitis onset to the scleral melting diagnosis.

This case highlights the importance of not only understanding prior ocular surgical history but also knowing potential long-term compilations of antimetabolites utilized in said procedures. In this case, the mitomycin C was not applied to the area of the RETISERT® implant, but approximately 2 clock hours away. Hence the scleral thinning was postulated to occur due to the combined effect of prior mitomycin C, the mechanical and corticosteroid effect of the RETISERT®, and ongoing use of topical difluprednate.

Conclusion

This case underscores the potential for delayed and severe complications arising from mitomycin C, even years after its application. Long-term vigilance is essential to identify and address adverse effects such as scleromalacia perforans and avascular necrosis. Understanding these risks highlights the need for ongoing patient monitoring and careful consideration of past treatments in managing complex ocular conditions.

Figure 1. Slit lamp photo of the temporal right eye demonstrating focal scleromalacia perforans, avascular necrosis, deep blue Prolene sutures from RETISERT®, and a calcific plaque.

Kaleb Abbott, OD, MS, is from the Department of Ophthalmology at the University of Colorado School of Medicine. He can be reached at Kaleb.abbott@cuanschutz.edu.

References

- Bick MW. Surgical treatment of scleromalacia perforans. AMA Arch Ophthalmol. 1959;61(6):907-917. doi:10.1001/archopht.1959.00940090909006

- Wu C-C, Yu H-C, Yen J-H, Tsai W-C, Liu H-W. Rare extra-articular manifestation of rheumatoid arthritis: scleromalacia perforans. Kaohsiung J Med Sci. 2005;21(5):233-235. doi:10.1016/S1607-551X(09)70193-7

- Wanjari MB, Lohakare T, Potdukhe A, Munjewar PK, Kantode VV. A rare occurrence of scleromalacia perforans with juvenile rheumatoid arthritis: a case report. Cureus. 2022;14(7):e27520. doi:10.7759/cureus.27520

- Reddy SC, Tajunisah I, Rohana T. Bilateral scleromalacia perforans and peripheral corneal thinning in Wegener’s granulomatosis. Int J Ophthalmol. 2011;4(4):439-442. doi:10.3980/j.issn.2222-3959.2011.04.22

- Evans PJ, Eustace P. Scleromalacia perforans associated with Crohn’s disease. Treated with sodium versenate (EDTA). Br J Ophthalmol. 1973;57(5):330-335. doi:10.1136/bjo.57.5.330

- Tesar PJ, Burgess JA, Goy JA, Lazell RW. Scleromalacia perforans in ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 1981;81(1):153-155.

- Luboń W, Luboń M, Kotyla P, Mrukwa-Kominek E. Understanding ocular findings and manifestations of systemic lupus erythematosus: update review of the literature. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(20):12264. doi:10.3390/ijms232012264

- Fukuda K, Mizobuchi T, Nakajima I, et al. Ocular involvement in relapsing polychondritis. J Clin Med. 2021;10(21):4970. doi:10.3390/jcm10214970

- Kopacz D, Maciejewicz P, Kopacz M. Scleromalacia perforans–what we know and what we can do. J Clinic Experiment Ophthalmol. 2013:S2. doi:10.4172/2155-9570.S2-009

- Galor A, Thorne JE. Scleritis and peripheral ulcerative keratitis. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2007;33(4):835-854, vii. doi:10.1016/j.rdc.2007.08.002

- Hata T, Hoshi T, Kanamori K, et al. Mitomycin, a new antibiotic from Streptomyces. I. J Antibiot (Tokyo). 1956;9(4):141-146.

- Mladenov E, Tsaneva I, Anachkova B. Activation of the S phase DNA damage checkpoint by mitomycin C. J Cell Physiol. 2007;211(2):468-476. doi:10.1002/jcp.20957

- Cumurcu T. Mitomycin-C use and complications in ophthalmology. International J Clinic Experiment Ophthalmol. 2017;1:029-032. doi:10.29328/journal.hceo.1001004

- Santhiago MR, Netto MV, Wilson SE. Mitomycin C: biological effects and use in refractive surgery. Cornea. 2012;31(3):311-321. doi:10.1097/ICO.0b013e31821e429d

- Singh P, Singh A. Mitomycin-C use in ophthalmology. IOSR Journal of Pharmacy. 2013;3(1):12-14.

- Vinod K, Gedde SJ, Feuer WJ, et al. Practice preferences for glaucoma surgery: a survey of the American Glaucoma Society. J Glaucoma. 2017;26(8):687-693. doi:10.1097/ijg.0000000000000720

- Smith S, D’Amore PA, Dreyer EB. Comparative toxicity of mitomycin C and 5-fluorouracil in vitro. Am J Ophthalmol. 1994;118(3):332-337. doi:10.1016/s0002-9394(14)72957-5

- Mermoud A, Salmon JF, Murray AD. Trabeculectomy with mitomycin C for refractory glaucoma in blacks. Am J Ophthalmol. 1993;116(1):72-78. doi:10.1016/s0002-9394(14)71747-7

- Akova YA, Koç F, Yalvaç I, Duman S. Scleromalacia following trabeculectomy with intraoperative mitomycin C. Eur J Ophthalmol. 1999;9(1):63-65. doi:10.1177/112067219900900110

Contact Info

Grandin Library Building

Six Leigh Street

Clinton, New Jersey 08809