Managing difficult-to-treat ocular surface disease with multiple cryopreserved amniotic membrane treatments

The contents of this article are informational only and are not intended to be a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment recommendations. This editorial presents the views and experiences of the author and does not reflect the opinions or recommendations of the publisher of Optometry 360.

By Damon Dierker, OD, FAAO

Ocular surface disease (OSD) requires targeted intervention to prevent progressive corneal damage and other complications. In many cases, artificial tears and topical medications are insufficient to repair and stabilize the ocular surface, and patients with refractory disease may need more advanced treatments.1 For such patients, and particularly those with dry eye disease (DED) and/or inflammation-related nerve damage, cryopreserved amniotic membranes (CAMs) may be especially useful, as they provide anti-inflammatory, anti-angiogenic, and antimicrobial effects; promote stem cell activity; and can repair damaged corneal nerves.2-4 Depending on the complexity and severity of the patient’s OSD, multiple CAM treatments may be needed to promote healing and restore ocular surface integrity.

OSD: a spectrum of ocular disorders

Despite encompassing a broad spectrum of disorders, corneal integrity and tear film stability are compromised in all cases of OSD.5 Disruptions in the homeostasis of the tear film may lead to chronic inflammation and tissue damage,6-8 which may further progress to corneal sequelae such as superficial punctate keratitis, filamentary keratitis, and non-healing epithelial defects, impacting vision and quality of life.7-9 If left untreated, these conditions may cause damage to corneal nerves, potentially leading to neurotrophic keratitis (NK) and further complicating management.6

Identifying high-risk patients: chronic OSD and the risk of NK

Early identification and targeted intervention for OSD are key to preventing progression and improving long-term outcomes. This is especially true for patients with systemic autoimmune conditions that may complicate ocular disease management, such as diabetes, rheumatoid arthritis, or Sjögren’s syndrome.10,11 Additional risk factors for chronic OSD include multiple prior ocular surgeries and prolonged use of preserved topical glaucoma medications.12,13 Patients with moderate-to-severe DED and compromised corneal health require closer monitoring, as these factors increase the risk of developing NK.

Once considered rare, NK is now recognized as more prevalent than previously thought; one study found that 58% of cataract surgery candidates with DED exhibited stage 1 NK.14 If left untreated, early-stage NK can worsen DED, which then iteratively contributes to corneal nerve dysfunction, creating a damaging cycle that inhibits healing.2,6,15,16

One of the most telling indicators of NK is persistent corneal staining that does not improve with lubricants or topical anti-inflammatory agents. However, an equally critical—yet often overlooked—factor is corneal sensitivity loss, which can signal early neurotrophic changes and should prompt immediate intervention to prevent further deterioration.17,18

I now emphasize corneal sensitivity testing far more than I did 5 years ago. Prompt detection and treatment of NK is necessary to prevent disease progression and ocular surface damage.18,19

Corneal sensitivity testing

Corneal sensitivity testing assesses nerve function by measuring responses to brief stimulation, categorizing sensitivity as absent, reduced, normal, or increased. Consider Galor et al’s protocol rating responses on a scale from 0 (no response) to 3 (hypersensitive response). Corneal sensation can be assessed clinically in all quadrants using a cotton wisp, dental floss, or tapered tissue if a quantitative esthesiometer is not available.20

CAM for refractory OSD

Assessing treatment history—what has worked and what has not—is essential in evaluating patients with refractory OSD. Most will have used lubricant drops and may have been prescribed topical corticosteroids or immunomodulators.1 Even if they have experienced partial symptom relief from such a regimen, a different modality may be required to address the ongoing disease process and tissue damage.

In addition, some patients struggle with the cost of prescribed treatments, while others face physical limitations that make administering eye drops or nasal sprays difficult. These barriers often lead to inconsistent adherence and suboptimal outcomes, further complicating management.21,22

CAM (Prokera®; BioTissue, Inc.) serves as a second-line therapy, not a last resort, and should be considered when conventional treatments fail to provide sufficient improvement.1 CAM may also be a better alternative than simply switching from 1 steroid or immunomodulator to another in patients who have received these treatments but have persistent symptoms.2,23 Patients who most benefit from CAM typically have chronic, rather than recent-onset, DED (in my clinic, ≥3 months of symptoms) and often have systemic inflammatory risk factors; patients with accompanying punctate or filamentary keratitis are also strong candidates.2,6

CAM preparations have been found to better preserve structural and biological components versus amniotic membranes that are dehydrated.4,24,25 Multiple studies have found that placement of CAM leads to the restoration of corneal epithelial health, improves visual acuity in eyes with NK and DED, and helps alleviate symptoms.2,23,26,27

For patients with severe stage 1 or early stage 2 NK, cenegermin (Oxervate®; Dompé U.S. Inc.) may be necessary, but obtaining approval can take time.28 During this waiting period, CAM can serve as an initial treatment to provide relief while approval is secured and, in some cases, may offer enough benefit to eliminate the need for cenegermin altogether. A phased approach—starting with CAM, transitioning to cenegermin if needed, and using CAM again for regression—ensures continuous care with minimal delays.

Multiple CAM treatments for moderate to severe cases

In cases of significant corneal disease or impaired nerve function, sequential CAM treatments may facilitate optimal recovery. While this may be a somewhat rare occurrence (<10% of my patients require multiple sequential CAMs), it is not uncommon for me to use multiple CAMs in the same patient or to use CAM over a period of 6 months to a year to manage flares. To illustrate the role of multiple CAMs in managing moderate-to-severe OSD, consider the 2 patient cases in FIGURE 1 and FIGURE 2.

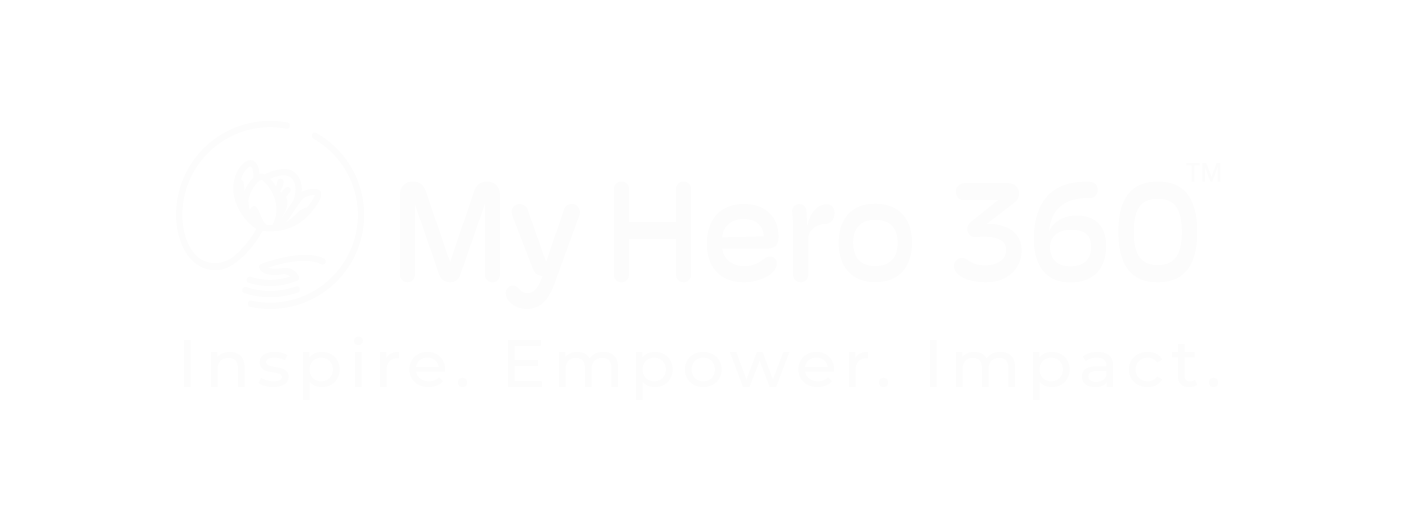

Figure 1. A 68-year-old male patient with chronic DED and diabetes came to the clinic after experiencing several weeks of worsening vision in his right eye (OD). Examination revealed a central epithelial defect (Figure 1a and Figure 1b) and reduced corneal sensitivity, leading to a diagnosis of stage 2 NK. He received two CAMs over 1 week to promote healing, successfully restoring his ocular surface (Figure 1c).

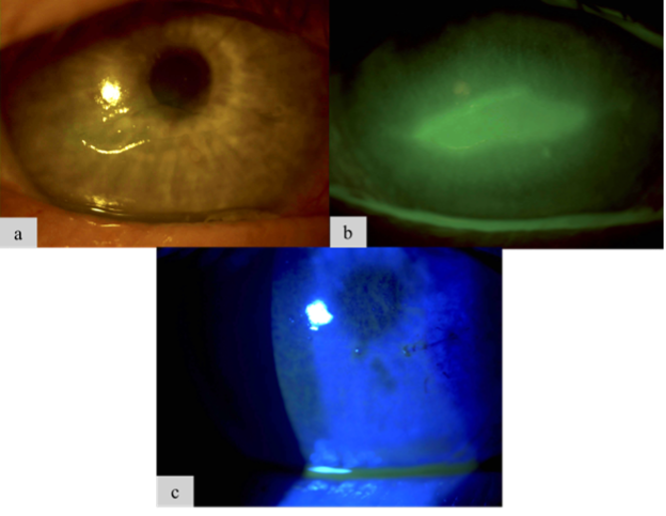

Figure 2. A 72-year-old female patient with chronic DED and rheumatoid arthritis struggled with multiple topical therapies due to lack of efficacy, difficulty with administration, and high costs. To provide more effective management, we adopted a provider-led intervention approach. She now receives CAM treatment every 6 to 12 months, which consistently helps control her symptoms and maintain her vision. Her OD ocular surface before (Figure 2a) and after CAM (Figure 2b) is shown here.

In such cases, clear documentation is essential for both reimbursement and patient communication. When counseling patients, I might say, “I can see that this is helping, but your eye hasn’t healed as much as we’d like. A second CAM treatment can provide additional support to help your cornea recover more fully.” I also reassure patients that there are typically no insurance issues, as CAM’s zero-day global period eliminates delays, allowing us to proceed immediately and provide ongoing care without interruption.29

It is important to note that CAM can be valuable for long-term management of DED flares, medication lapses, or for patients who prefer in-office interventions over self-administered treatments. Scheduling should remain flexible, considering practical factors like transportation, caregiving responsibilities, and work commitments. A proactive approach with sequential or periodic CAM use helps preserve vision, prevent complications, and support long-term ocular health.

Conclusion

Many patients with chronic OSD can struggle for years, losing the ability to enjoy daily activities like reading or watching a grandchild’s ballgame. My main focus for these patients is preventing vision loss and improving quality of life. CAM can offer a rapid, effective adjunct for patients who have found insufficient relief with other treatments, and it works very well as a complement to prescription therapies, procedures, and other supportive treatments.

Damon Dierker, OD, FAAO, is the Director of Optometric Services at Eye Surgeons of Indiana. He is the founder of Dry Eye Boot Camp and cofounder of Eyes On Dry Eye, both of which are educational programs for eyecare professionals. He can be reached at damon.dierker@esi-in.com.

Disclosures: Dr. Dierker is a paid consultant for AbbVie, Alcon, Azura, Bausch + Lomb, BioTissue, Bruder, Dompé, Nordic Pharma, NuSight Medical, ScienceBased Health, Sight Sciences, Sun Pharma, Tarsus, Théa Pharmaceuticals, and Viatris.

References

- Jones L, Downie LE, Korb D, et al. TFOS DEWS II management and therapy report. Ocul Surf. 2017;15(3):575-628. doi:10.1016/j.jtos.2017.05.006

- Mead OG, Tighe S, Tseng SCG. Amniotic membrane transplantation for managing dry eye and neurotrophic keratitis. Taiwan J Ophthalmol. 2020;10(1):13-21. doi:10.4103/tjo.tjo_5_20

- Jirsova K, Jones GLA. Amniotic membrane in ophthalmology: properties, preparation, storage and indications for grafting-a review. Cell Tissue Bank. 2017;18(2):193-204. doi:10.1007/s10561-017-9618-5

- Tighe S, Mead OG, Lee A, Tseng SCG. Basic science review of birth tissue uses in ophthalmology. Taiwan J Ophthalmol. 2020;10(1):3-12. doi:10.4103/tjo.tjo_4_20

- Stapleton F, Alves M, Bunya VY, et al. TFOS DEWS II epidemiology report. Ocul Surf. 2017;15(3):334-365. doi:10.1016/j.jtos.2017.05.003

- Craig JP, Nichols KK, Akpek EK, et al. TFOS DEWS II definition and classification report. Ocul Surf. 2017;15(3):276-283. doi:10.1016/j.jtos.2017.05.008

- Bron AJ, de Paiva CS, Chauhan SK, et al. TFOS DEWS II pathophysiology report [published correction appears in Ocul Surf. 2019;17(4):842. doi:10.1016/j.jtos.2019.08.007.]. Ocul Surf. 2017;15(3):438-510. doi:10.1016/j.jtos.2017.05.011

- Rao SK, Mohan R, Gokhale N, Matalia H, Mehta P. Inflammation and dry eye disease-where are we? Int J Ophthalmol. 2022;15(5):820-827. doi:10.18240/ijo.2022.05.20

- Yang S, Lee HJ, Kim DY, Shin S, Barabino S, Chung SH. The use of conjunctival staining to measure ocular surface inflammation in patients with dry eye. Cornea. 2019;38(6):698-705. doi:10.1097/ICO.0000000000001916

- Naik K, Magdum R, Ahuja A, et al. Ocular surface diseases in patients with diabetes. Cureus. 2022;14(3):e23401. doi:10.7759/cureus.23401

- Stern ME, Schaumburg CS, Dana R, Calonge M, Niederkorn JY, Pflugfelder SC. Autoimmunity at the ocular surface: pathogenesis and regulation. Mucosal Immunol. 2010;3(5):425-442. doi:10.1038/mi.2010.26

- Versura P, Giannaccare G, Pellegrini M, Sebastiani S, Campos EC. Neurotrophic keratitis: current challenges and future prospects. Eye Brain. 2018;10:37-45. doi:10.2147/EB.S117261

- Andole S, Senthil S. Ocular surface disease and anti-glaucoma medications: various features, diagnosis, and management guidelines. Semin Ophthalmol. 2023;38(2):158-166. doi:10.1080/08820538.2022.2094714

- Hovanesian JA. The THINK study: testing hypoesthesia and the incidence of neurotrophic keratopathy in cataract patients with dry eye. Clin Ophthalmol. 2024;18:3627-3633. doi:10.2147/OPTH.S501452

- Tepelus TC, Chiu GB, Huang J, et al. Correlation between corneal innervation and inflammation evaluated with confocal microscopy and symptomatology in patients with dry eye syndromes: a preliminary study. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2017;255(9):1771-1778. doi:10.1007/s00417-017-3680-3

- Labetoulle M, Baudouin C, Calonge M, et al. Role of corneal nerves in ocular surface homeostasis and disease. Acta Ophthalmol. 2019;97(2):137-145. doi:10.111/aos.13844

- NaPier E, Camacho M, McDevitt TF, Sweeney AR. Neurotrophic keratopathy: current challenges and future prospects. Ann Med. 2022;54(1):666-673. doi:10.1080/07853890.2022.2045035

- Sacchetti M, Lambiase A. Diagnosis and management of neurotrophic keratitis. Clin Ophthalmol. 2014;8:571-579. doi:10.2147/OPTH.S45921

- Neurotrophic Keratopathy Study Group. Neurotrophic keratopathy: an updated understanding. Ocul Surf. 2023;30:129-138. doi:10.1016/j.jtos.2023.09.001

- Galor A, Lighthizer N. Corneal sensitivity testing procedure for ophthalmologic and optometric patients. J Vis Exp. 2024;(210). doi:10.3791/66597

- Mehuys E, Delaey C, Christiaens T, et al. Eye drop technique and patient-reported problems in a real-world population of eye drop users. Eye (Lond). 2020;34(8):1392-1398. doi:10.1038/s41433-019-0665-y

- Hovanesian J, Singh IP, Bauskar A, Vantipalli S, Ozden RG, Goldstein MH. Identifying and addressing common contributors to nonadherence with ophthalmic medical therapy. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2023;34(Suppl 1):S1-S13. doi:10.1097/ICU.0000000000000953

- McDonald MB, Sheha H, Tighe S, et al. Treatment outcomes in the DRy Eye Amniotic Membrane (DREAM) study. Clin Ophthalmol. 2018;12:677-681. doi:10.2147/OPTH.S162203

- Rodríguez-Ares MT, López-Valladares MJ, Touriño R, et al. Effects of lyophilization on human amniotic membrane. Acta Ophthalmol. 2009;87(4):396-403. doi:10.111/j.1755-3768.2008.01261.x

- Cooke M, Tan EK, Mandrycky C, He H, O’Connell J, Tseng SC. Comparison of cryopreserved amniotic membrane and umbilical cord tissue with dehydrated amniotic membrane/chorion tissue. J Wound Care. 2014;23(10):465-476. doi:10.12968/jowc.2014.23.10.465

- John T, Tighe S, Sheha H, et al. Corneal nerve regeneration after self-retained cryopreserved amniotic membrane in dry eye disease. J Ophthalmol. 2017;2017:6404918. doi:10.1155/2017/6404918

- McDonald M, Janik SB, Bowden FW, et al. Association of treatment duration and clinical outcomes in dry eye treatment with sutureless cryopreserved amniotic membrane. Clin Ophthalmol. 2023;17:2697-2703. doi:10.2147/OPTH.S423040

- Prescribing information. Dompé U.S. Inc. Revised December 2024. https://www.oxervate.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/OXERVATE-PI-Rev.-12-2024.pdf

- Corcoran Consulting Group. Reimbursement for Prokera. Published August 8, 2022. Accessed March 3, 2025. https://corcoranccg.com/reimbursement-for-proker/

Contact Info

Grandin Library Building

Six Leigh Street

Clinton, New Jersey 08809